Seal Beach, California

Seal Beach, California | |

|---|---|

Historic Mission Revival Seal Beach City Hall | |

Location of Seal Beach within Orange County, California. | |

Location within Greater Los Angeles | |

| Coordinates: 33°45′33″N 118°4′57″W / 33.75917°N 118.08250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Orange |

| Incorporated | October 27, 1915[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council/city manager[2] |

| • Mayor | Thomas Moore[3] |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Schelly Sustarsic |

| • City Council | Joe Kalmick[4] Nathan Steele[5] Lisa Landau[6] |

| • City Manager | Jill R. Ingram |

| Area | |

• Total | 11.80 sq mi (30.56 km2) |

| • Land | 11.27 sq mi (29.19 km2) |

| • Water | 0.53 sq mi (1.38 km2) 13.45% |

| Elevation | 13 ft (4 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 25,242 |

| • Density | 2,100/sq mi (830/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 90740 |

| Area code | 562 |

| FIPS code | 06-70686 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1661416, 2411851 |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Anaheim Landing[10] |

| Reference no. | 219 |

Seal Beach is a coastal city in Orange County, California, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 25,242, up from 24,168 at the 2010 census.

Seal Beach is located in the westernmost corner of Orange County. To the northwest, just across the border with Los Angeles County, lies the city of Long Beach and the adjacent San Pedro Bay. To the southeast are Huntington Harbour, a neighborhood of Huntington Beach, and Sunset Beach, also part of Huntington Beach. To the east lie the city of Westminster and the neighborhood of West Garden Grove, part of the city of Garden Grove. To the north lie the unincorporated community of Rossmoor and the city of Los Alamitos. A majority of the city's acreage is devoted to the Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach military base.[11]

History

[edit]Indigenous

[edit]The Tongva village of Motuucheyngna was located in what is now Seal Beach in the area of the Los Cerritos Wetlands. It was part of the greater area of Puvungna, which was a major ceremonial and regional trading center for the Tongva and Acjachemen. Villagers used te'aats to travel out to villages on Pimu (Santa Catalina Island) and other islands off the coast, now referred to as the Channel Islands.[12][13] In 2003, a burial site of the village was disturbed in a 196-acre (79 ha) Seal Beach residential development, Hellman Ranch, that was met with opposition from the Tongva.[14]

Anaheim Landing

[edit]Beginning in the mid-1860s, the eastern area of what is now Old Town Seal Beach became known as Anaheim Landing. A warehouse and wharf had been built on a small bay where Anaheim Creek emptied into the Pacific Ocean. It was established by farmers and merchants in the newly settled town of Anaheim who wanted a closer, more convenient port to ship the wine they were growing and also to receive items they needed to help build homes and buildings in their new town.[15]

For a few years Anaheim Landing came close to rivaling San Pedro for its volume of shipping, but the arrival of the railroad in Anaheim in 1875 made it easier to ship product via the rails than by hauling a wagon overland across 12 miles (19 km) of soft soil to the Landing. The beaches and surrounding rolling Anaheim Landing had by this time become popular as a getaway from hot summer days. Los Angeles newspapers talk of a permanent summer population of as many as 400 and even more on special days.[15]

The landing was also home to a number of fishing boats that plied the local fishing areas. This activity was written about by Nobel-prize winning author Henryk Sienkiewicz in a short essay, "The Cranes."[15] The site of Anaheim Landing is now registered as a California Historical Landmark.[10]

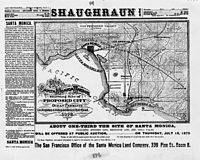

In 1903 Los Angeles realtor Philip A. Stanton, very familiar with the area from his time selling land in Anaheim, and Huntington Beach and also from representing the local real estate interests of banker (and Pacific Electric Railroad co-owner) Isaias W. Hellman, put together a syndicate to lay out the town of Bayside on the land between Anaheim Landing and Anaheim Bay and the eastern edge of Alamitos Bay.[16]

Real estate development

[edit]The new town would be situated along the still not-announced Balboa Line of the Pacific Electric, which would run from Long Beach to Newport Beach. As there was already a town called Bayside in Northern California (by Eureka), Stanton's group instead called their new town Bay City. Due to many factors—including competition from other beach resort areas (Long Beach, Redondo Beach and Venice/Ocean Park/Santa Monica), some national financial crises, and the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, which sent most investment dollars to the more lucrative rebuilding of San Francisco—Bay City failed miserably as a real estate investment.[16]

In 1913, Stanton optioned the land to real estate promoter Guy M. Rush, who invested in building a renovated pier with pavilions on either side. Rush also re-branded the town as Seal Beach and marketed it via postcards and advertisements around the country. This too failed and by early 1915, Rush had let his options lapse. In 1915 Stanton tried again, arranging to obtain some amusements from the closing San Francisco Panama-Pacific International Exposition and rebuild them as part of new amusement area which would be called The Joy Zone.[16]

As part of this plan, the Bayside Land Company led a campaign to incorporate the town (October 27, 1915) and then had the new city council approve legal drinking in the town. This made it different from the Pike at Long Beach, which was a "dry city." The Joy Zone, a beach-side amusement park built in 1916, was the first in Orange County.[16] It achieved some brief popularity, but the US entry into World War I and the resulting restrictions on rubber and metal dramatically impacted the amusement area.

After the war, Prohibition impacted the town's value as an amusement resort. After 1920, the town's location on two bays, with many inlets to offload bootleg liquor, its small police department, and its location on the county line, allowed it to become a popular place for rumrunners, then gamblers. From 1928 to 1939, the town had as many as six gambling establishments on Main Street. In addition, most of Southern California's famous gambling ships (Johanna Smith, Rose Isle, Johanna Smith II, SS Caliente, SS Tango, Showboat, Mt. Baker) operated off the Seal Beach, just over the line from Long Beach.[17]

With gambling being a misdemeanor, the trials were held in the town's municipal court and a Seal Beach jury never returned a guilty verdict, to the dismay of Orange County and Long Beach officials. But circa 1941, with significant pressure being put on the gamblers by State Attorney General Earl Warren, most of the Seal Beach gambling and ships ended. Their absence was soon filled by a former Los Angeles police detective named William L. Robertson.[17]

World War II

[edit]In early 1944. during World War II, the Navy purchased most of the land around Anaheim Landing to construct the United States Navy's Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach for loading, unloading, and storing of ammunition for the Pacific Fleet, and especially those US Navy warships home-ported in Long Beach and San Diego. With closure of the Concord Naval Weapons Station in Northern California, it has become the primary source of munitions for a majority of the United States Pacific Fleet.[18] The arrival of the Navy catalyzed a growth in population which eventually succeeded in shutting down Robertson's gambling operations.

Surfing has always had a presence in Seal Beach. Newspaper advertisements showing surfers were part of Guy M. Rush's "Seal Beach" campaign of 1913. The town hosted the mainland's first surfing competition—it was at a private gathering of the annual Minnesota Picnic. But its popularity really took off after the war with the arrival of legendary surfer Blackie August, who taught many of the local kids how to surf. August's son, Robert, was one of the pair of surfers featured in the classic surf film, Endless Summer. Local legends Jack Haley and Mike Haley were the winners of the first two national surfing championships.

-

Seal Beach amusement park, 1920.

-

Anaheim Landing aerial photo, circa 1930s

-

Anaheim Landing 1891

2011 shooting

[edit]The deadliest mass killing in Orange County history occurred in Seal Beach. On October 12, 2011, a mass shooting took place at the local Salon Meritage hair salon. Eight people inside the salon and one person in the parking lot were shot, and only one victim survived.[19] The suspect in the shooting, 41-year-old Scott Evans Dekraai, was arrested without incident[20][21] and charged with eight counts of murder and one count of attempted murder.[22] Prior to the shooting, there had been only one murder in Seal Beach during the previous four years.[23]

Geography

[edit]Seal Beach is located at 33°45′33″N 118°4′57″W / 33.75917°N 118.08250°W (33.759283, -118.082396).[24]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.0 square miles (34 km2). 11.3 square miles (29 km2) of it is land and 1.8 square miles (4.7 km2) of it (13.45%) is water.

Seal Beach is bounded by the CDP of Rossmoor and the city of Los Alamitos to the north, the West Garden Grove neighborhood and city of Westminster to the east, Huntington Beach to the east and south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west.[25]

Climate

[edit]Seal Beach has a semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh) with Mediterranean characteristics.

| Climate data for Seal Beach, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

101 (38) |

107 (42) |

109 (43) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

97 (36) |

89 (32) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

68 (20) |

68 (20) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

77 (25) |

81 (27) |

83 (28) |

81 (27) |

78 (26) |

72 (22) |

68 (20) |

74 (23) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 46 (8) |

48 (9) |

50 (10) |

53 (12) |

57 (14) |

61 (16) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

58 (14) |

51 (11) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

34 (1) |

37 (3) |

39 (4) |

48 (9) |

50 (10) |

58 (14) |

54 (12) |

52 (11) |

45 (7) |

37 (3) |

29 (−2) |

20 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.98 (76) |

3.04 (77) |

2.50 (64) |

0.65 (17) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.11 (2.8) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.39 (9.9) |

1.15 (29) |

1.75 (44) |

13.14 (334) |

| Source: [26][27][28] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 669 | — | |

| 1930 | 1,156 | 72.8% | |

| 1940 | 1,553 | 34.3% | |

| 1950 | 3,553 | 128.8% | |

| 1960 | 6,994 | 96.8% | |

| 1970 | 24,441 | 249.5% | |

| 1980 | 25,975 | 6.3% | |

| 1990 | 25,098 | −3.4% | |

| 2000 | 24,157 | −3.7% | |

| 2010 | 24,168 | 0.0% | |

| 2020 | 25,242 | 4.4% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 24,937 | −1.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[29] | |||

2020

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[30] | Pop 2010[31] | Pop 2020[32] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 20,372 | 18,580 | 16,814 | 84.33% | 76.88% | 66.61% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 329 | 255 | 370 | 1.36% | 1.06% | 1.47% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 54 | 38 | 53 | 0.22% | 0.16% | 0.21% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,363 | 2,273 | 3,624 | 5.64% | 9.40% | 14.36% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 37 | 52 | 46 | 0.15% | 0.22% | 0.18% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 21 | 62 | 91 | 0.09% | 0.26% | 0.36% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 427 | 577 | 1,091 | 1.77% | 2.39% | 4.32% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,554 | 2,331 | 3,153 | 6.43% | 9.64% | 12.49% |

| Total | 24,157 | 24,168 | 25,242 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census[33] reported that Seal Beach had a population of 24,168. The population density was 1,853.3 inhabitants per square mile (715.6/km2). The racial makeup of Seal Beach was 20,154 (83.4%) White (76.9% Non-Hispanic White),[34] 279 (1.2%) African American, 65 (0.3%) Native American, 2,309 (9.6%) Asian, 58 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 453 (1.9%) from other races, and 850 (3.5%) from two or more races. There were 2,331 Hispanic or Latino residents, of any race (9.6%).

The Census reported that 23,943 people (99.1% of the population) lived in households, 22 (0.1%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 203 (0.8%) were institutionalized.

There were 13,017 households, out of which 1,866 (14.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 4,891 (37.6%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 788 (6.1%) had a female householder with no husband present, 283 (2.2%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 383 (2.9%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 66 (0.5%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. Of the households, 6,312 (48.5%) were made up of individuals, and 4,340 (33.3%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.84. There were 5,962 families (45.8% of all households); the average family size was 2.65.

In Seal Beach there were 3,151 people (13.0%) under the age of 18, 1,176 people (4.9%) aged 18 to 24, 4,076 people (16.9%) aged 25 to 44, 6,513 people (26.9%) aged 45 to 64, and 9,252 people (38.3%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 57.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 78.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 76.3 males.

There were 14,558 housing units at an average density of 1,116.4 per square mile (431.0/km2), of which 9,713 (74.6%) were owner-occupied, and 3,304 (25.4%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.4%. 17,689 people (73.2% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 6,254 people (25.9%) lived in rental housing units.

During 2009–2013, Seal Beach had a median household income of $51,242, with 9.9% of the population living below the federal poverty line.[34]

2000

[edit]As of the census[35] of 2000, there were 24,157 people, 13,048 households, and 5,884 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,099.5 inhabitants per square mile (810.6/km2). There were 14,267 housing units at an average density of 1,240.0 per square mile (478.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.91% White, 1.44% African American, 0.30% Native American, 5.74% Asian, 0.18% Pacific Islander, 1.28% from other races, and 2.16% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.43% of the population.

There were 13,048 households, out of which 13.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.2% were married couples living together, 5.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.9% were non-families. Of all households, 48.8% were made up of individuals, and 34.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.83 and the average family size was 2.65.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 13.3% under the age of 18, 4.0% from 18 to 24, 21.5% from 25 to 44, 23.7% from 45 to 64, and 37.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 54 years. For every 100 females, there were 78.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $42,079, and the median income for a family was $72,071. Males had a median income of $61,654 versus $41,615 for females. The per capita income for the city was $34,589. About 3.2% of families and 5.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.2% of those under age 18 and 5.3% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

The major employer in Seal Beach is Boeing, employing roughly 1,000 people. Its facility was originally built to manufacture the second stage of the Saturn V rocket for NASA's Apollo crewed space flight missions to the Moon and for the Skylab program. Boeing Homeland Security & Services (airport security, etc.) is based in Seal Beach and Boeing Space & Intelligence Systems (satellite systems and classified programs) is headquartered in Seal Beach.

Top employers

[edit]According to the city's 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[36] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boeing | 1,000 |

| 2 | MagTek | 250 |

| 3 | Siemens Medical Solutions | 200 |

| 4 | Target | 200 |

| 5 | First Team Real Estate | 150 |

| 6 | Farmers & Merchants Bank of Long Beach | 150 |

| 7 | Bixby Ranch Company | 135 |

| 8 | Kohl's | 121 |

| 9 | Spaghettini Grill and Lounge | 105 |

| 10 | Albertsons | 100 |

| 11 | Custom Building Products | 96 |

| 12 | Autism Partnership | 95 |

| 13 | P2F Holdings | 85 |

| 14 | Health Net | 75 |

| 15 | Original Parts Group | 75 |

| 16 | BakerCorp | 71 |

Arts and culture

[edit]

Annual cultural events

[edit]The Lions Club Pancake Breakfast in April and its Fish Fry (started in 1943) in July are two of the biggest events in Seal Beach. There has been a Rough Water Swim the same weekend as the Fish Fry since the 1960s. The Seal Beach Chamber of Commerce sponsors many events, including: a Classic Car Show in April, a Summer Concert series once every week in July and August, the Christmas Parade in December along with Santa and the Reindeer. Also in the fall is the Kite Festival in September. The Taste for Los Al, which since 2001 has been benefitting activities at Los Alamitos High School (home high school for Seal Beach students), takes place every October and has one of the largest silent auctions in the nation, often having over 100 tables.

Music

[edit]The record label Mash Down Babylon Records is based in Seal Beach, operated out of a garage known as The Elizabethan. The label was founded by Matt Embree, lead vocalist and guitarist in the Seal Beach-based progressive rock/post-hardcore band RX Bandits.

Other points of interest

[edit]

On Electric Avenue where the railroad tracks used to run, there is the Red Car Museum which features a restored Pacific Electric Railway Red Car.[16][37] The Balboa Line once passed through Seal Beach going south to the Balboa Peninsula in Newport Beach. Going north into Long Beach a rider could then take the Red Cars through much of Los Angeles County.[38] Anderson Street Water Tower is a restored 1892 water tower that is being rented for overnight stays.

Seal Beach is also home to the Bay Theatre, which was a popular venue for independent film and revival screenings. It was closed in 2012 but was purchased in 2017 by Paul Dunlap who is currently restoring it.

The Seal Beach National Wildlife Refuge is located on part of the Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach. Much of the refuge's 911 acres (3.69 km2) is the remnant of the saltwater marsh in the Anaheim Bay estuary (the rest of the marsh became the bayside community of Huntington Harbour, which is part of Huntington Beach). Three endangered species, the Ridgway's light-footed rail, the California least tern, and the Belding's Savannah sparrow, can be found nesting in the refuge. With the loss and degradation of coastal wetlands in California, the remaining habitat, including the Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve in Huntington Beach and Upper Newport Bay in Newport Beach, has become much more important for migrating and wintering shorebirds, waterfowl, and seabirds. Although the refuge is a great place for birdwatching, because it is part of the weapons station, access is limited and usually restricted to once-a-month tours.

Recreation

[edit]

The second longest wooden pier in California (the longest is in Oceanside)[16][39] is located in Seal Beach and is used for fishing and sightseeing. The pier has periodically suffered severe damage due to storms and other mishaps, requiring extensive reconstruction. A plaque at the pier's entrance memorializes Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works, 1938, Project No. Calif. 1723-F, a rebuilding necessitated by storms in 1935. Another plaque honors the individuals, businesses, and groups who helped rebuild the pier after a storm on March 2, 1983, tore away several sections. A "Save the Pier" group formed in response to an initial vote by the City Council not to repair the pier. The ensuing outcry of dismay among residents caused the City Council to reverse its stance while claiming the city lacked the necessary funds. Residents mobilized and eventually raised $2.3 million from private and public donors to rebuild the pier.

Surfing locations in Seal Beach include the Seal Beach pier and the river-"Stingray Bay" (or Ray Bay—the surfer's nickname for the mouth of the San Gabriel River—the stingrays are attracted by the heated water from several upstream powerplants). Classic longboard builders in the area include Harbour Surfboards, established in 1959, in Seal Beach.

Government and politics

[edit]The city is administered under a council-manager form of government, and is governed by a five-member city council serving four-year alternating terms. The mayor and mayor pro tempore are chosen by and from the council.[40]

Seal Beach's municipal jail offers a pay for stay program in which offenders who would normally go to county jails could stay at Seal Beach's jail for a price.[41]

State and federal representation

[edit]In the California State Senate, Seal Beach is in the 36th Senate District, seat currently vacant. in the California State Assembly, Seal Beach is split between the 70th Assembly District, represented by Republican Tri Ta, and the 72nd Assembly District, represented by Republican Diane Dixon.[42]

In the United States House of Representatives, Seal Beach is in California's 47th congressional district, represented by Democrat Dave Min.[43]

Education

[edit]Seal Beach is almost entirely in the Los Alamitos Unified School District, and a small portion outside of that district is on the reservation of Seal Beach Naval Weapons Station.[44]

Seal Beach once had its own elementary school district and sent its older children to Huntington Beach or Marina High School in the Huntington Beach Union High School District. Since the early 1980s it has been part of the Los Alamitos Unified School District.

Younger students (K-5) go to McGaugh Elementary School, Hopkinson Elementary School, Rossmoor Elementary, Lee Elementary, Los Alamitos Elementary or Weaver Elementary. Students in grades 6–8 attend either Oak Middle School or McAuliffe Middle School. High school students go to Los Alamitos High School, which is a Gold Ribbon School. Until 2000, the Orange County High School of the Arts was part of Los Alamitos High School. In 2000, the school district suffered a major blow when the community lost the Orange County High School of the Arts to Santa Ana, where it is now located.[45]

Notable people

[edit]- Andrija Artuković, Nazi collaborator convicted of war crimes.[46]

- Robert August, one of the two surfers in Bruce Brown's classic surf film The Endless Summer, grew up in Seal Beach.[47]

- Jimmy Bennett, Actor, born in Seal Beach. Portrayed Captain Kirk (during his childhood) in Star Trek.[48]

- Sean Collins, founder of Surfline.[49]

- Susan Egan, actress/singer, starred in broadway productions including the role of Belle from Beauty and the Beast also does voice work most notably Meg from Disney's Hercules, born in Seal Beach.

- Matt Embree, vocalist/guitarist of the band RX Bandits and founder of the Mash Down Babylon Records record label, both of which are also based in Seal Beach.

- Steve Goodman, singer-songwriter and author of "City of New Orleans", "A Dying Cubs Fan's Last Request" and "You Never Even Call Me By My Name" made Seal Beach his home from 1980 until his death in 1984.[50]

- Bill Green, former U.S. and NCAA record holder in Track and Field, 5th place in the hammer throw at the 1984 Olympic Games lived in Seal Beach from 1988 to 1999

- Jack Haley, Jr. - former NBA player[51]

- Chris Kluwe, punter for the Minnesota Vikings of the NFL

- Greg Knapp, New York Jets pass game specialist.[52]

- Pat McCormick, a two-time Olympic platform and springboard gold medal diver (1952 & 1956).[53]

- Jack Snow, Notre Dame and Los Angeles Rams football player[54]

- Clayton Snyder, actor who played Ethan Craft in the Lizzie McGuire TV show and film.

- Michelle Steel, U.S. Congresswoman from California's 48th district since 2021 (resident of Surfside Colony), former Chair of the Orange County Board of Supervisors.

- Randy Stonehill, Grammy nominated singer/songwriter resides in Seal Beach with wife Sandi

- Chad Wackerman, rock and jazz drummer who has worked with Frank Zappa, Barbra Streisand, James Taylor and many others

- Bill Ward, drummer, solo artist, and occasional lead vocalist of hard rock/heavy metal band, Black Sabbath.[55]

- Bob Welch, professional baseball player[56]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "CITY OF SEAL BEACH CITY COUNCIL". City of Seal Beach. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "Thomas Moore". Voter's Edge. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Nguyen, Chris (January 31, 2019). "Democrat Kalmick Defeats Republican Amundson in Seal Beach Council Run-Off". OC Political. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Elattar, Hosam (February 2, 2023). "Nathan Steele and Lisa Landau Maintain Leads in Seal Beach Runoff Election". Voice of OC. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Elattar, Hosam (February 2, 2023). "Nathan Steele and Lisa Landau Maintain Leads in Seal Beach Runoff Election". Voice of OC. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Seal Beach". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "Seal Beach (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Anaheim Landing". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Google Maps".

- ^ Lewinnek, Elaine (2022). A people's guide to Orange County. Gustavo Arellano, Thuy Vo Dang. Oakland, California. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-520-97155-4. OCLC 1226813397.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Tribal Cultural Landscape" (PDF). Tribal Cultural Resources: 7. May 2020.

- ^ Reyes, David (January 19, 2003). "Developer, Native Americans Are at Odds Over Burial Site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c Strawther, Larry (2014). Seal Beach: A Brief History. Charleston, SC: History Press. pp. 20–25.

- ^ a b c d e f Mellen, Greg (October 17, 2015). "From sin city roots to quiet enclave, Seal Beach considers its future at 100 years". Orange County Register.

- ^ a b Strawther, Larry (2014). Seal Beach: A Brief History. Charleston, SC: History Press. pp. 95–99, 106–112. ISBN 978-1-62619-489-2.

- ^ "Naval Weapons Station Seal Beach". www.cnic.navy.mil. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- ^ "8 Slain in O.C.'S Deadliest Mass Killing (video)". The Orange County Register. October 12, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Gunman kills 8 at Seal Beach salon. Los Angeles Times, October 12, 2011.

- ^ California shooting: Eight killed at Seal Beach salon BBC News, October 13, 2011.

- ^ "Seal Beach shootings: Death penalty sought". The Orange County Register. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "8 Dead in O.C.'S Deadliest Mass Killing". The Orange County Register. October 12, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "City Boundaries". Orange County GIS. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "Zipcode 90740". www.plantmaps.com. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Records and Averages for Seal Beach, California". www.msn.com. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Seal Beach, CA Climate". www.myforecast.co. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Seal Beach city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Seal Beach city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Seal Beach city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Seal Beach city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Seal Beach (city) Quickfacts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ City of Seal Beach CAFR

- ^ "Red Car Museum - Seal Beach - Red Car Artifacts - Old Photos". BeachCalifornia.com. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- ^ Staff (May 12, 2015). "A look at the trains that built the O.C. coast". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ California Coastal Resource Guide. California Coastal Commission. 1987. p. 352. ISBN 9780520061866.

- ^ "Government". City of Seal Beach. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Santo, Alysia; Victoria Kim; Anna Flagg (March 9, 2017). "This is like paradise': Seal Beach's pay-to-stay program actively markets its jail, attracting deep-pocketed offenders". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ "California Districts". UC Regents. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "California's 47th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Orange County, CA" (PDF). p. 1 (PDF p. 2/5). Retrieved November 24, 2024. - Text list

- ^ Alexander, Karen; Meier, James (August 25, 1999). "Arts High School Now Considering a Santa Ana Site". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 25, 2009.

- ^ Dizdar, Zdenko; Grčić, Marko; Ravlić, Slaven; Stuparić, Darko (1997). Tko je tko u NDH. Minerva.

- ^ Cannell, Michael (September 18, 1995). "Chairman Of The Longboard". Sports Illustrated. Time Warner. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0796366/?ref_=nm_knf_i4 [user-generated source]

- ^ Connelly, Laylan (December 26, 2011). "Surfline founder Sean Collins dies". The Orange County Register. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ Kinchen, David M. (May 27, 2007). "BOOK REVIEW: Clay Eals Crafts Ultimate Biography of Immensely Influential Songwriter/Performer Steve Goodman". Huntington News.Net. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ Djanseziang, Kevork (March 17, 2015). "Seal Beach's Jack Haley, who played for UCLA, Chicago Bulls, Lakers, dead at 51". The Orange County Register. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ "Broncos Hire Former Raider Coach". January 18, 2013.

- ^ Carpenter, Eric (August 3, 2008). "Memories as good as gold". The Orange County Register. pp. News 6.

- ^ Eubanks, Lon (August 31, 1995). "Stopping the Snow Melt : Ram Broadcaster Trying to Get Acclimated to New Life With the Team in a Hot, Steamy Town". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ Boehm, Mike (August 19, 1998). "A Black Day Dawning". Los Angeles Times. pp. F–2. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (June 11, 2014). "Bob Welch, Pitching Ace and Rangy Prototype for Today's Power Arms, Is Dead at 57". The New York Times. p. B11. Retrieved June 11, 2014.